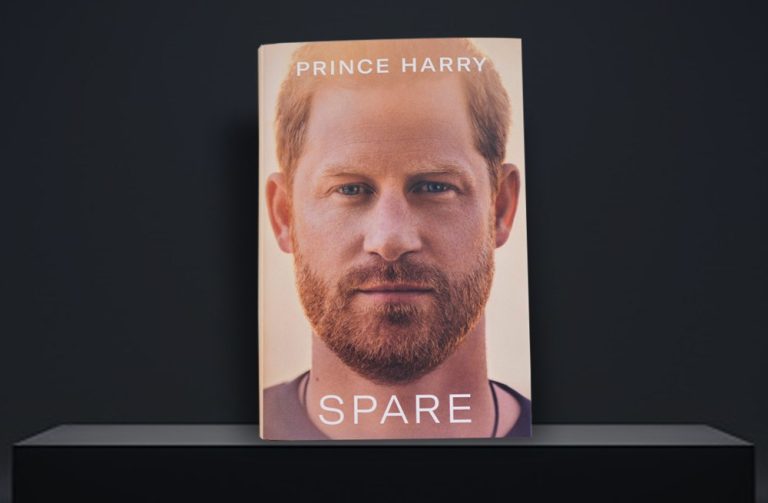

THE first revelation is his name. It is not Harry. He was christened Henry Charles Albert David. His memoirs Spare appear under his more popular name: Prince Harry.

Spare is a wordy remonstrance by Harry against fate for being the second born after Prince William and against his family for their lack of understanding of his errant personality, and later ungenerous slights against his wife Meghan.

The book has been ghostwritten by J.R. Moehringer. After reading more than 400 pages of Harry’s stream of consciousness revelations and grievances, the reader might be forgiven for suspecting that many persons added their own drops of acid to the ink.

His American editors, for one. They encourage Harry to include gratuitous references to the late Duchess of Windsor — “the notorious Wallis Simpson”, and to him standing with his father Charles and elder brother William in the Royal Burial Ground at Frogmore (Windsor), “our feet almost on top of Wallis Simpson’s face”.

In that unlikely graveyard setting, the three have a showdown. There, Harry recalls, “Willy in particular didn’t want to hear anything. After he’d shut me down several times, he and I began sniping, saying some of the same things we’d said for months — years. It got so heated that Pa [Charles] raised his hands. Enough! He stood between us, looking up at our flushed faces: Please, boys — don’t make my final years a misery.”

“All at once something shifted inside of me. I looked at Willy, really looked at him, maybe for the first time since we were boys. I took it all in: his familiar scowl, which had always been his default in dealings with me; his alarming baldness, more advanced than my own; his famous resemblance to Mummy, which was fading with time. With age. In some ways he was my mirror, in some ways he was my opposite. My beloved brother, my arch nemesis, how had that happened?”

An insider yet outside the royal family, Prince Harry felt closer to those distant from him in age — to Gan-Gan (his great-grandmother the Queen Mother) who treated him “with love and humour and respect”; to Granny (the late Queen Elizabeth II) for her “imperturbable serenity” and for “tapping and swaying” through the deafening Jubilee concert, wearing ear-plugs; Grandpa (Prince Philip) for “his many passions — carriage driving, barbecuing, shooting, food, beer [and] the way he embraced life.”

Oscar Wilde once said that when we are young, we love our parents; as we grow older, we judge them; rarely if ever do we forgive them. Towards his father Charles, Harry is ambivalent. “He was always sniffing things. Food, roses, our hair. He must’ve been a bloodhound in another life”, or “He’d always given an air of being not quite ready for parenthood — the responsibilities, the patience, the time [.] But single parenthood? Pa was never made for that.”

Occasionally, Harry is forgiving: “To be fair, he tried. Evenings, I’d shout downstairs: Going to bed, Pa! He’d always shout back cheerfully: I’ll be there shortly, darling boy! True to his word, minutes later he’d be sitting on the edge of my bed. He never forgot that I didn’t like the dark, so he’d gently tickle my face until I fell asleep.”

For Harry, his mother was a star — “light, pure and radiant light”. He feels her omnipresence, sees her everywhere, even in a leopard in the African bush: “That leopard was clearly a sign from her, a messenger she’d sent to say: All is well. And all will be well.” He spares her ‘friends’, referring to Dodi Fayed as Mr ‘Blah-Blah’.

Once Meghan enters Harry’s narrative, the book bristles with banalities: the squabble between Catherine and Meghan over bridesmaids’ dresses, Meghan’s intrusive reference to Catherine’s post-partum hormones, even Meghan borrowing Catherine’s lip-gloss: “Kate, taken aback, went into her handbag and reluctantly pulled out a small tube. Meg squeezed some onto her finger and applied it to her lips. Kate grimaced.”

The denouement within the family occurred at the Sandringham Summit in January 2020, when Harry and Meghan’s decision to quit was discussed. Also present were two unctuous courtiers who guided the royals to a foregone decision.

A royal biographer had once written: “It is courtiers who make royalty frightened and frightening.” Harry labels three nasty ones the Bee, the Fly and the Wasp — “middle-aged white men who’d managed to consolidate power through a series of bold Machiavellian manoeuvres [,] each taking advantage of a Queen in her nineties, enjoying his influential position while merely appearing to serve.”

Prince Harry’s memoirs will have as many admirers in the US as detractors in the UK. Spare is already a best seller. When counting his royalties, though, Prince Harry should recall Francois Truffaut’s advice: “Airing one’s dirty linen never makes for a masterpiece.”