Review by AZ

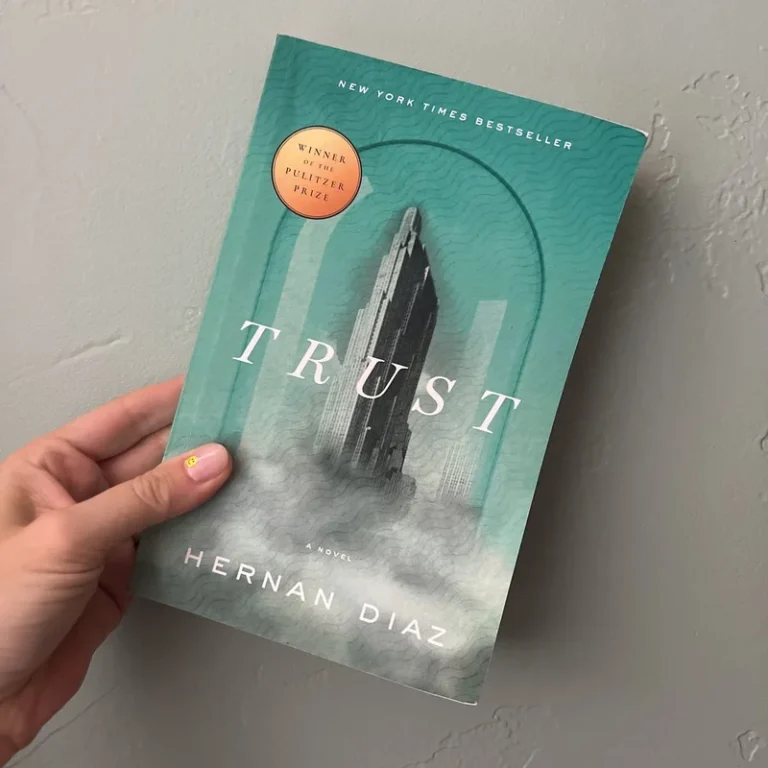

The novel Trust revolves around a wealthy childless couple from Manhattan, New York called Andrew and Mildred Bevel in the form of four short stories. The short stories are arranged as a novella, a fractional memoir, a memoir of that memoir, and a journal.

A finance giant in the early 20th century, Bevel has created a huge fortune for himself. His biography is part ofTrust’s first act, “Bonds,” a thinly obscure novella written by Harold Vanner, an unimportant author, who diligently records the financial myth of Benjamin and Helen Rask, also a childless, prosperous Manhattan couple – their lavish Fifth Avenue mansion, the shady deals that sustain them through the 1929 crash.

Throughout the roaring ’20s, Rask accumulates riches and Helen becomes a patron of the arts. Then, comes the Crash of 1929. Since Rask profits from other speculators’ losses, rumours circulate that he engineered the Crash and he and Helen are coldblooded people.

The final chapters of this saga detail Helen’s ordeal as a patient at a psychiatric institute in Switzerland; her mania and her eczema, described as a “merciless red flat monster gnawing on her skin,” are reminiscent of the reallife torments of Zelda Fitzgerald.

Trust, the title refers not only to financial trust but also to the trust humans place in each other, the contract between reader and author. As Vanner writes of Rask, “He created a trust meant exclusively for the working man… A schoolteacher or farmer could then settle her or his debt in comfortable monthly payments.” But the social bonds in “Bonds” melt as Rask, sensing the Crashdecided to make gains through the marginalised and economically low income groups.

In the second section of Trust, Bevel speaks for himself. He became truly angry by the publication of Bonds in 1938, following the death of his beloved Mildred, and is determined to write his memoir to show the truth.

However, he cannot help revealing his family’s riches, his vacations, and the fantastic wealth accumulated by generations. He leaves gaps in each chapter, which indicate the acquisition of wealth of those less unfortunate or facing economic crisis by unsavoury means. Bevel tries hard to present himself as a serious working man but the author shows him in his true colours i.e. someone who did not have much to do with his fortune except for inheriting it.

Trust propels the novel’s third section, told by Ida Partenza, an elderly literary journalist who, in her own memoir, reflects on the genesis of her career, when Bevel hired her as a secretary to shape his manuscript. She’s kept the secrets of her employment through the decades.

In the 1980s, she learns that Andrew and Mildred’s personal papers have been archived in their former Upper East Side mansion, now a Frick-like museum. Her curiosity gets the better of her as she needs to discover if the papers reveal a side different from hers.

The comparison of her earlier work in a working class neighbourhood with Andrew and its transformation in the present not only makes us see two different time periods but also the transitions in society. Her working class father hated money, yet did not mind his daughter working for a rich man.

Bevel’s life was the source for Vanner’s best-selling novel, Bonds, and he was enraged by it so he removed it from the New York public library system. He also hired Ida to help him write a memoir that would set the record straight. The fourth and final section of Trust is wired with revelations, exposing the underlying hypocrisy.

During her time with Bevel, rendered in flashback, Ida marvels at the financier’s arrogance and selfdelusion: “It was also of great importance to him to show the many ways in which his investments had always accompanied and indeed promoted the country’s growth.… Business was a form of patriotism.”

Although Ida is from a lower socio-economic stratum, Bevel respects her talent and honesty. It, however, does not stop him from borrowing anecdotes/incidents from her life to help her embellish his memoir.

Mildred’s journal, Futures,brings us to the conclusion. She doesn’t have a future, but she’s very keen on recording the past and present. She is very clear in her journal about the level of discomfort and unease which existed between her husband and herself.

The novel is both seeped in history as wellas harbours a postmodern point. Throughout, Diaz makes a connection between the realms of fiction and finance. Money is what forms the background and what Bevel strives for. All the money in the world cannot save Mildred, however is she the genius or her husband?

As Ida’s father, the Italian anarchist, says: “Money is a fantastic commodity. You can’t eat or wear money, but it represents all the food and clothes in the world. This is why it’s a fiction.”